Some South Woodford scribbles from DD, our resident diarist, commentator and observer of all things local

Dear readers, something different this issue. Twenty years ago, after much urging, my mother recorded her life story. I think that nothing could be more appropriate to share with you in these extraordinary times than this first part of her account…

In July 1909, I was born in Romford, Essex, the first child of my parents, who were both 21 years of age. I was christened Beryl Joy. My brother Hugh was born in 1910.

My earliest recollection was going on holiday to Great Yarmouth. My father’s business was concerned with bookstalls on railway stations and he had a free pass on the LNER, the London North Eastern Railway, which was a consideration as we had little money. The main attractions for us children were the Punch and Judy show and a phrenologist, who had a roped-off area and read the ‘bumps’ on people’s heads for sixpence. We sat on the sand and listened. The other fascination was a man who etched lovely designs on the beach, such as the Houses of Parliament or the royal family, and was rewarded with pennies in his cap by onlookers. He used the firm, flat sand left by the receding tide, which went out a very long way, but of course, his work was washed away when the tide came in again.

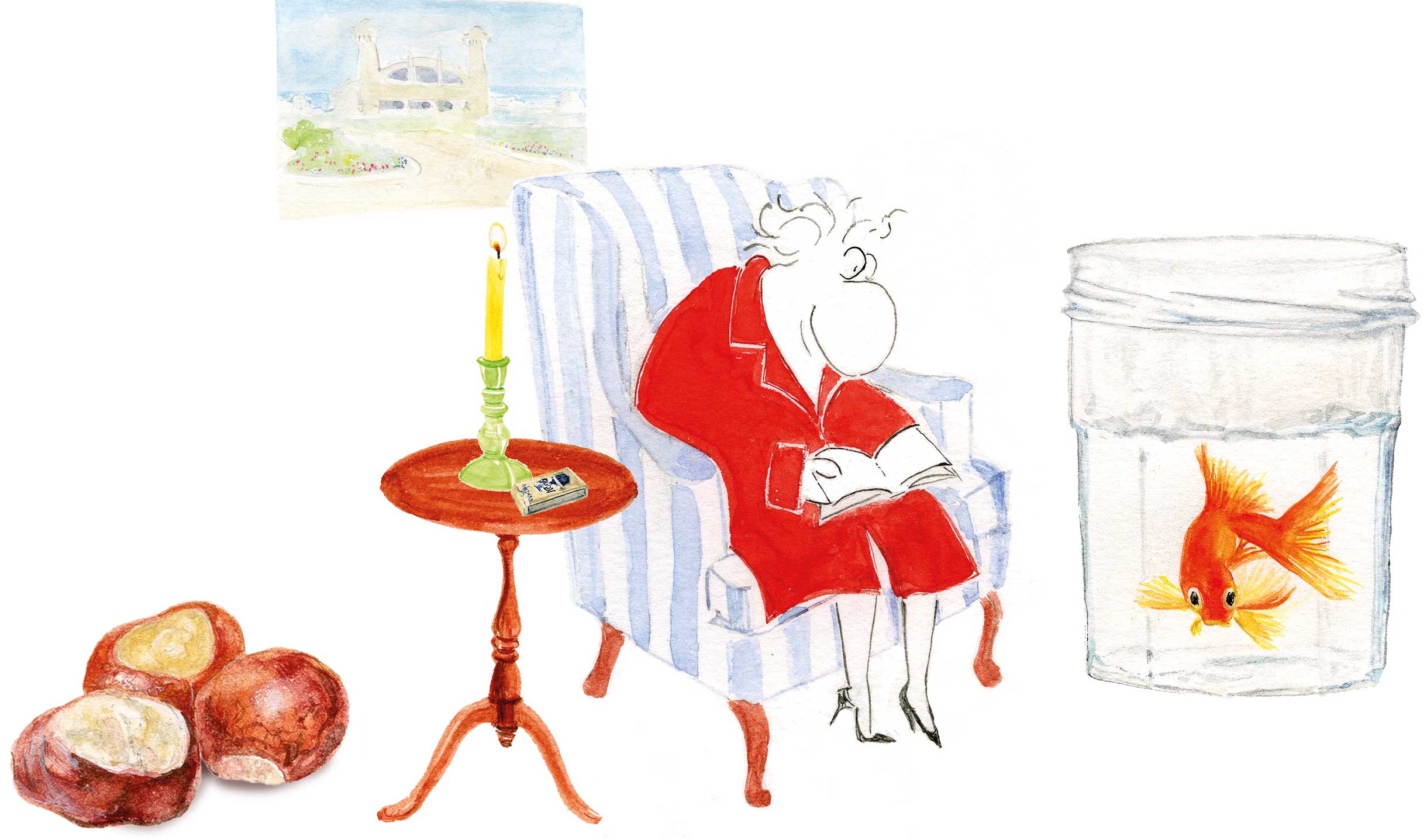

We moved to Leytonstone in 1913. I was anxious to see the new house, rented. It was a corner house with a front and back-gate entrance. Next day, I glued myself to the front-room window. I watched the children going to school and wished I was with them. The ‘rag and bone man’ with his barrow called on Saturday. He cried out and the children brought rags and old clothes and a jam jar filled with water, and were rewarded with a goldfish. A rabbit skin produced threepence. Plenty of people kept rabbits for extra meat. (Years later, I had a beautiful collar made out of a rabbit skin.) Another special person was the lamplighter, who came every evening on his bicycle with a long pole on his left shoulder. He lit the street lights, fitted with gas mantels. On Sunday, the muffin man came, ringing an enormous bell, selling his muffins for Sunday tea. These were all highlights for me.

There was no gas or electricity upstairs. The bedrooms were so cold! In the kitchen, there was a stove with oven at the side. In this oven, three bricks were placed every day, and at bedtime, these were wrapped in old flannel and carried up by us to keep our feet warm in bed. We also carried a lighted candle. I often wonder how we didn’t set the house on fire.

At last, the day came for me to go to school. Very eager. No tears! And I was introduced to my teacher, Miss Calder. I was happy. We had coal fires in the classroom, which often went out, and lessons were interrupted when the caretaker was called, which often took a long time. At six years I moved on to Miss Preston. I really liked her. I confided in her one morning that I had a new baby sister, Ruby, and she replied: “You would like to make something for her,” and suggested a bonnet. So, I had my first introduction to knitting, which I found easy. The teacher provided the wool and ribbon strings, and it was duly presented.

What did children do to amuse themselves? In the street, it was hopscotch, conkers, skipping ropes, bowling wooden hoops, or, if your family was more affluent, a wooden scooter. The owner of a scooter allowed you to have a ride occasionally. Indoors, especially at weekends or on wet days, we played Ludo, Snakes and Ladders, Happy Families and my favourite game, Up Jenkins. And, of course, cards. We children played several card games by seven or even six years old.

At seven, my mother decided I would do better at Kirkdale School. This was across the main Leytonstone High Road and it was thought I could manage this alone. It wasn’t crowded with traffic like it is now. The headmistress of Kirkdale was very elegant and looked like Queen Mary, wore a toque and carried a long umbrella. All the children at Kirkdale were taught to speak beautifully. One afternoon, we were to go for a nature ramble in the forest. It was discovered I had no hat. I had to report to the headmistress. No Kirkdale girl was allowed in the street in a ‘crocodile’ without one. I was allowed to accompany them, minus a hat, but with a warning.

Then, war with Germany was declared. I remember the noise of the guns, the air raids, getting up in the middle of the night when the sirens went. In 1917, my father had to join the forces and went off to France. My mother returned to her teaching and her young sister, Nora, came to look after us. I suppose she wasn’t more than 15, the eighth or possibly ninth child in the family. I now had another sister, Audrey, aged six months. Food was in very short supply: meat, fresh fruit, vegetables. We all suffered from a lack of vitamins. In 1918, there was a terrible outbreak of Spanish flu. My mother, who had been teaching on supply, had often to walk long distances to schools in bad weather (no cars in those days!) and she caught the flu and then double pneumonia, and died. She was 31. At the time, to be frank, it seemed quite normal. I wasn’t amazed. The lady next door had died and the daughter of the man in the off-licence and several children in my class at school. The enormity of what had happened hit me later.

I was nine years old, Hugh was eight, Ruby, four and Audrey, 18 months. My father was in France, not able to get home for the funeral.

What was my future?

To contact DD about the conclusion to her mother’s story, email dd@swvg.co.uk